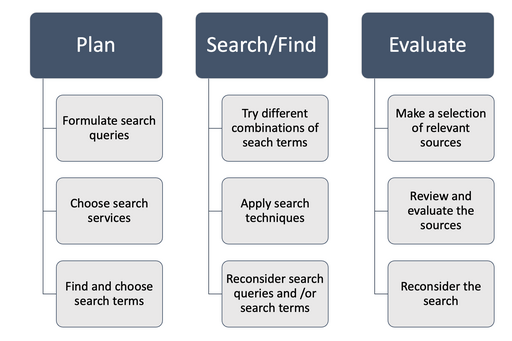

The structured search process

This page outlines the process of a structured search, which is made in three stages; planning, search/retrieval, and assessment.

Planning

Defining quieries

Before you start searching for information, it is important that you have defined a question for your research, a query. The query is the basis for all your searches. You define it by delimiting and clearly defining your research problem. In the course of your work, you will likely adjust your query as you gain more in-depth knowledge of the subject.

Once you have a query, it is time to consider your information needs. Your query points to one or more topics. You probably won’t need to find sources on everything within these topics, but you need to select the aspects that are relevant to you. Consider your target audience and whether there is a particular time period that is important to include in your search.

Select discovery services

Which search engine, library catalogue or database should you choose? Your subject obviously matters for your choice, but there are other factors to consider, too.

Discovery services can be subject-specific or cover several fields. This is why you need to know what kind of information you are looking for. You will probably have to use several discovery services to find enough quality sources. The services commonly used for scholarly material are different in nature and give you access to different types and amounts of resources. They all have their strengths and weaknesses. This means the choice of discovery services is an important step in your search process.

Find and select terms

If you are searching within a new area or research field, it is wise to identify important key terms used in that particular field. Study encyclopaedias, handbooks, general textbooks and student papers to get a solid background for your work, and collect key terms.

Most search engines will only retrieve results for the exact word you use. For example, if you enter “environment” you will miss “environmental issues”. For this reason, consider your search terms carefully before you start searching. Keep in mind

- possible synonyms

- singular/plural

- correct spelling

- spelling varieties (particularly US vs UK terms; such as color and colour)

- inflections

Search/retrieve – advanced strategies

Once you have defined your query, identified the best discovery services and selected your search terms, it is time to make a more systematic search effort.

At this stage, you may benefit from having made a few quick searches. The simpler and more general ones are a way to quickly get your bearings within a particular field. Finding the information needed for an in-depth search within a specific research area is often time-consuming. To save time and frustration, it is a good idea to document your searches:

- Write down where you have been searching, and which combinations of search terms you have used.

- Reference management software can be helpful when gathering and organising your finds.

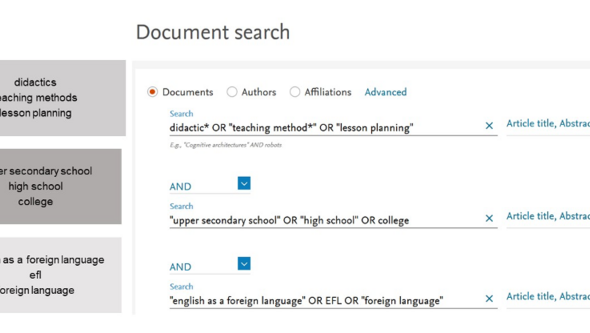

Try different combinations of search terms

Combinations of search terms with AND/OR, phrase searches, truncation and metadata field searches are known as search strings. Build these using a couple of your search terms together. Depending on how happy you are with the results, you can change the search terms you used, to get different results, or add additional search terms to reduce the number of results.

Below are some of the most common and useful techniques to direct and refine your search.

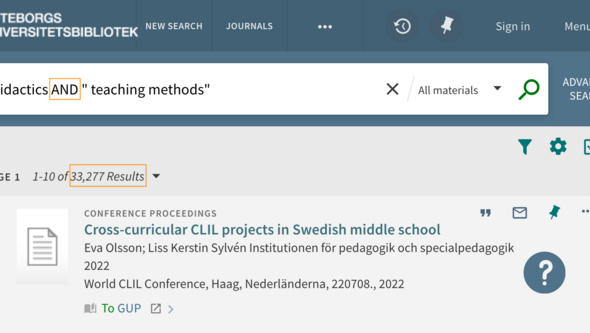

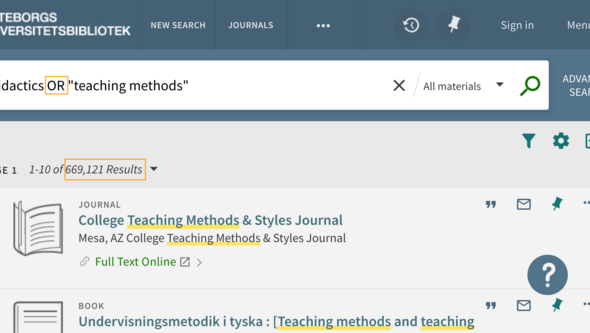

Combine search terms with AND/OR

By combining your search terms in different ways, you can narrow or expand your search. You can do this by using AND/OR:

- didactics AND “teaching methods”

AND limits your results. All search terms must be included in the results. Most search engines automatically perform an AND search. For this reason, avoid using too many search terms at once. Instead, start with one or two and then add one search term at a time. - didactics OR “teaching methods”

OR expands your search and yields more results. It is enough if one of the search terms is present in the results. This is useful when you want to include synonyms for your search term.

Truncation – one way of expanding your search results

Truncation means searching for a word stem, with different endings. Truncation is often done with an asterisk (*). Some search engines offer automatic truncation. Search engines such as Google and Google Scholar do not allow truncation. In library catalogues and databases, you decide whether the search term should be truncated or not. Keep in mind that unwanted endings and combinations may also be included in the results.

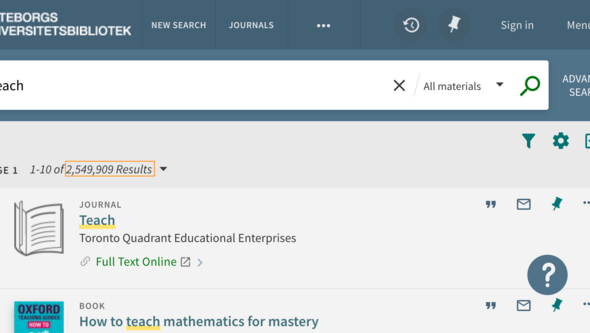

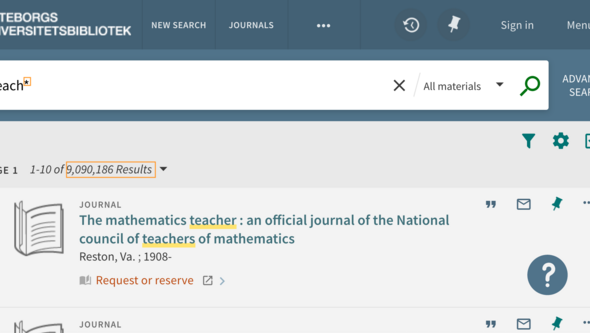

Example: teach* = teach, teaches, teaching, teacher, teachers…

Truncation can yield a lot of results, but in combination with other search terms, truncation can be useful to broaden one or more terms. Try it out!

Phrase search – for compound terms

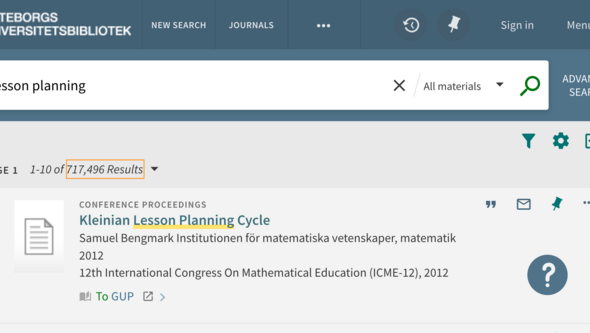

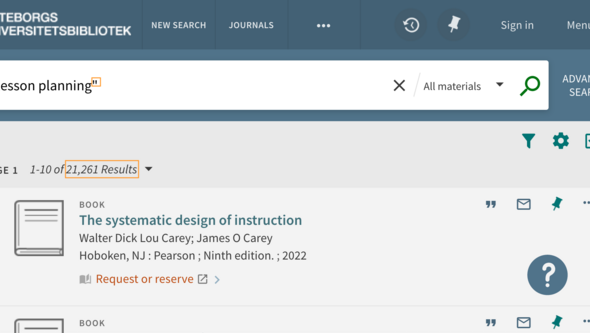

When searching for compound terms, you need to use phrase searching. Put the words in quotation marks, i.e. “lesson planning” to keep them together. Phrase searching limits the number of results to materials that are actually about lesson planning. Avoid irrelevant results where “lesson” and “planning” occur separately in the text, which may be about something completely different.

Fields search – advanced search

Many discovery services offer an advanced search mode. By entering your search terms in various fields in the advanced search interface, you may choose to search for a title, an author, a subject term or something else. Through an advanced search, you control where in the results your search terms should appear. An advanced search will limit your results.

Citation search – find later research

A citation search means that you start from a publication you have found, and find out if some other scholar has referred to it in their own research. Searching in this way uncovers more recent research in the same field. To track citations, use a search service that records references.

Citation searches are currently available through the article databases Scopus and Web of Science (available to users affiliated with Gothenburg University) and the Google Scholar search engine (freely available).

After your search – reasses!

When you have been searching for a while, it is a good idea to review your query and search terms. If you haven’t found enough sources, your query may be too narrow, or your search terms may be too specific. If you have found too much material – consider whether the question is too broad, or the search terms too general.

Source assessment

When writing texts as part of your education, you will use different types of sources as a starting point for your work. These may include books, scientific articles or information found on websites. Whatever the source, it is important that you examine it critically and evaluate its relevance to your topic.

Source critical questions

When reviewing printed and digital sources, there are a few questions you can ask yourself to assess their reliability:

- Is there a named author or editor, and can you confirm their authority in the field?

- What is the purpose of the contents? Is the author aiming to inform, impact, provoke, or maybe sell?

- Who is the intended target audience, and does the difficulty level match your purpose?

- When was the material compiled, and has it been recently updated? Are there any newer editions?

- How trustworthy are the contents? How well does the source cover the subject? Do you perceive the text as objective? If there are any references in the text and the reading list, are they relevant?

Focus: Online source criticism

Reviewing websites is essentially about trying to determine whether the content is credible and whether you can trust the author or publisher. One way to get an idea of reliability is to check the information in certain parts of the website.

The criteria for reviewing online material are the same as for printed material, but there are some additional things you should check:

Remember to compare with other sources!

You should always consider whether the source is relevant to your subject.